Key Messages

Key Messages

![]() Download these notes as a PDF:

Download these notes as a PDF:

DfE Topic 3 Child Development Final 17/10/14 Combined notes

![]() Download these notes as a Word document:

Download these notes as a Word document:

DfE_Topic 3 Child Development Key Messages Final 17/10/14

Download the questions and exercises as a Word 97-2003 DOC file:

DfE_Topic 3 Child Development Key Messages Final 17/10/14 Word 97-2003

Topic 3: Child development

Key Messages

- Social workers need to have a good understanding of child development in order to recognise normative patterns of development and be alert to issues of concern.

- Social workers need to communicate with other professionals to gain a holistic picture of the child’s developmental progress over time.

- There are number of theoretical approaches to understanding child development. These theories underpin many child and family interventions that promote positive child development.

- The quality of inter-parental relationships and parenting practices are important factors in children’s development. Parental problems such as domestic violence, substance misuse and mental ill-health can have an impact on all aspects of children’s development.

- Contemporary research highlights effective targets for intervention and prevention programmes aimed at remedying negative family influences on development.

Why is knowledge about child development important?

Social workers’ limited training and knowledge about child development has been highlighted in a number of recent studies (eg Brandon et al, 2011; Davies and Ward, 2012), as well as in the Munro Interim Report (Munro, 2011). The Curriculum Framework: Planning Supporting Permanence (CPD) highlights the importance of training in relation to child development, with a particular focus on developmental progress, continuities and discontinuities, the child’s timescales and to the role of the social worker in supporting children’s development in placement (Schofield and Simmonds, 2013).

All practitioners who have contact with children need to have good knowledge and understanding of the fundamentals of child development. This underpinning knowledge is essential to safeguarding children and the promotion of their well-being. It is also a vital component of family support, assessment and planning interventions (Brandon et al, 2011).

Social workers do not need to be experts in child development. However, they do need to be able to recognise patterns of overall development and be able to detect when a child’s development may be going ‘off track’ or developmental ‘milestones’ missed. Social workers also need to work closely with colleagues from different professional groups who do have particular expertise in order to review children’s developmental progress (Brandon et al, 2011). These include health visitors, community nursing staff, GPs, school staff, paediatricians and specialist therapists.

Contextualising the study of child development

The study of child development examines the changes (and the processes underpinning those changes) that begin at conception and continue throughout infancy, childhood and adolescence and into emerging adulthood.

Developmental progression (physical growth, the development of a secure attachment relationship, the acquisition and development of language, the development of adaptive social/peer relationship behaviours) explores the trajectories that underpin processes of normal development. Understanding normal development is a pre-requisite to understanding aspects or patterns of abnormal development.

Many influences can help shape a child’s development. Some are internal and integral to the child, such as genetic factors. Others are external – such as physical, psychological and family influences, and wider neighbourhood and cultural factors. Disabled children, including those with learning disabilities, may have a different rate of progress across the various developmental dimensions. And traumatic events, such as abuse or neglect, can lead to disruption in the developmental processes. Subsequent influences on a child can either ameliorate or exacerbate the effect of early damage (Open University et al, 2007; Department of Heath et al, 2000).

Poverty has a pernicious impact on child development. Children living in poverty have poorer physical health and high proportions of specific problems including:

- speech difficulties

- eyesight problems

- toothache

- obesity

- behavioural difficulties including, for example, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

(Sullivan and Joshi, 2008; Webster-Stratton et al, 2008; Séguin et al, 2007)

Online support for parents, carers and adopters

Many parents and carers turn to the internet to learn about what to expect, how children progress and develop, and what is ‘normal’. A few years ago, researchers at the Department of Paediatrics, Imperial College, London reviewed child development websites, testing them against a number of criteria including accuracy, readability, design and navigability (Williams et al, 2008). Among those at the top of their list were:

The Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need

For professionals, the statutory guidance Working Together to Safeguard Children (DfE, 2013) remains underpinned by reference to The Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families (Department of Health et al, 2000), which sets out the dimensions of a child’s developmental needs. These are reproduced in the box below:

Dimensions of a child’s developmental needs

Health

Includes growth and development as well as physical and mental well-being. The impact of genetic factors and of any impairment should be considered. Involves receiving appropriate health care when ill, an adequate and nutritious diet, exercise, immunisations where appropriate and developmental checks, dental and optical care and, for older children, appropriate advice and information on issues that have an impact on health, including sex education and substance misuse.

Education

Covers all areas of a child’s cognitive development which begins from birth.

Includes opportunities: for play and interaction with other children; to have access to books; to acquire a range of skills and interests; to experience success and achievement. Involves an adult interested in educational activities, progress and achievements, who takes account of the child’s starting point and any special educational needs.

Emotional and behavioural development

Concerns the appropriateness of response demonstrated in feelings and actions by a child, initially to parents and caregivers and, as the child grows older, to others beyond the family.

Includes nature and quality of early attachments, characteristics of temperament, adaptation to change, response to stress and degree of appropriate self-control.

Identity

Concerns the child’s growing sense of self as a separate and valued person.

Includes the child’s view of self and abilities, self-image and self-esteem, and having a positive sense of individuality. Race, religion, age, gender, sexuality and disability may all contribute to this. Feelings of belonging and acceptance by family, peer group and wider society, including other cultural groups.

Family and social relationships

Development of empathy and the capacity to place self in someone else’s shoes.

Includes a stable and affectionate relationship with parents or caregivers, good relationships with siblings, increasing importance of age-appropriate friendships with peers and other significant persons in the child’s life and response of family to these relationships.

Social presentation

Concerns a child’s growing understanding of the way in which appearance, behaviour, and any impairments are perceived by the outside world and the impression being created.

Includes appropriateness of dress for age, gender, culture and religion; cleanliness and personal hygiene; and availability of advice from parents or caregivers about presentation in different settings.

Self-care skills

Concerns the acquisition by a child of practical, emotional and communication competencies required for increasing independence. Includes early practical skills of dressing and feeding, opportunities to gain confidence and practical skills to undertake activities away from the family and independent living skills as older children.

Includes encouragement to acquire social problem-solving approaches. Special attention should be given to the impact of a child’s impairment and other vulnerabilities, and on social circumstances affecting these in the development of self-care skills.

(reproduced from Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families – Department of Health et al, 2000: p19)

Theories of child development: a brief review

Frameworks that set out to explain what underpins child development can be classified into specific theories. Such theories provide a coherent view of the complex influences underpinning child development and offer guidance for practical issues encountered by parents, teachers, therapists and others concerned with promoting positive child development.

Child development theories may be categorised into five primary domains (for a good general source on development see Stassen Berger and Thompson, 1995):

- psychoanalytic theories

- learning theories

- cognitive theories

- ethological theories

- ecological theories.

1 Psychoanalytic (psychodynamic) theories: Beginning with the work of Sigmund Freud and his colleagues, psychoanalytic theory interprets human development in terms of intrinsic drives, many of which are unconscious. Though hidden from our awareness, these drives are viewed as influencing every aspect of a person’s thinking and behaviour. Freud identified three stages which occur in the first six years of life and are fundamental to healthy personality development: the oral stage from age 0 to 2 years; the anal stage at 2 to 3 years; and the phallic stage, from 3 to 5 years of age. Psychodynamic theory ‘offers a way of understanding how personality forms and develops through life and provides a theory for assessing emotional needs’ (The Developing World of the Child: Seeing the child – Open University et al, 2007).

2 Learning theories: Learning theories move away from a focus on intrinsic drives to the assessment of directly observable measures and behaviours. Learning theories explore the relationship between a stimulus (an experience or event) and a response (the behavioural reaction to that experience).

3 Cognitive theories: Cognitive theories focus on the structure and development of thought processes and the way these processes affect a person’s understanding of their social context and environment. Building on Freud’s ideas of stage-based development, they emphasise how progression (in terms of aptitude and understanding) is age related.

Cognitive theories consider how the development of understanding explains the nature of understanding itself and, importantly, the expectations created at different ages, and how this understanding affects an individual’s behaviour. Stages identified by the psychologist Jean Piaget include:

| Developmental stage | Age of normal development |

| Sensorimotor stage | 0-2 years |

| Pre-operational | 2-6 years |

| Concrete operational | 7-11 years |

| Formal operational | 12+ years |

Social learning theory combines cognitive theory with learning theory. Proposed by Bandura, social learning theory recognises that learning can occur through direct observation and modelling (imitation) of behaviour. Observational or social learning is dependent on four inter-related processes: observation (this is largely environmental), retention (cognitive – the ability to store information is important for the learning process), reproduction (cognitive – performing or practising the observed behaviour), and motivation (which is both environmental and cognitive – motivational processes are key to understanding why people employ the behaviour they have observed). Social learning theory is important in analysing how family processes influence child development and how individuals learn and adapt. ‘Behavioural interventions and cognitive behavioural work have been developed from social learning theory’ (The Developing World of the Child: Seeing the child – Open University et al, 2007).

4 Ethological theories: Ethological theories focus on how responsiveness to the environment varies across the lifespan and the effect of the environment on development. They build on the stage-based principles of psychoanalytic and cognitive theories, but focus on what are known as ‘sensitive periods’ rather than fixed, age-based developmental stages. Perhaps the best-known ethological perspective is attachment theory.

Attachment theory was first developed by John Bowlby and is a widely used approach for studying individual differences in child adjustment and factors affecting the quality of family interactions (for more information, see Topic 2 Key Messages on ‘Attachment Theory and Research’). Over the first 12 to 18 months of life, infants learn which of their own behaviours elicit desired responses from their caregiver. Infants then adapt their behaviours to fit those of their caregiver, resulting in parent-child attachments of varying quality. An internal working model of relationships is formed based on the young child’s early interactions with their caregivers, which guides the child’s future relationships. Recent research has called into question the fixed predictions of attachment theory in relation to long-term developmental outcomes for children (Rutter, 1981).

5 Ecological theories: Ecological theories identify the environmental systems with which an individual interacts and highlight how this interplay explains differences in individual development. Ecological perspectives underpin conceptual frameworks for assessing children’s needs (e.g. the Common Assessment Framework) as well as community-based programmes (such as Sure Start) that aim to improve children’s health and development by improving the context in which they grow up.

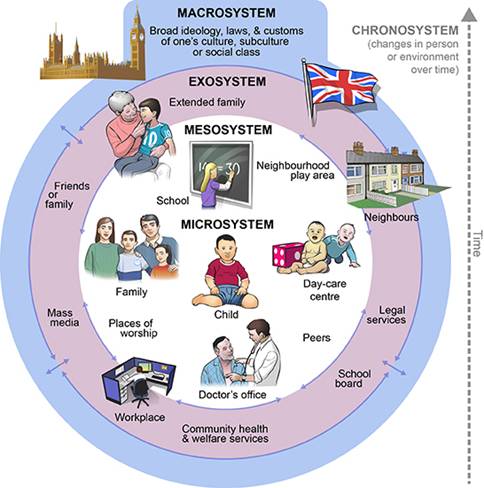

The best-known ecological theory is that of Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979), whose ecological systems theory explains how everything in a child’s environment affects growth and development. He labelled different levels of the environment as shown in the illustration:

Image source: Bronfenbrenner, ecological systems theory, King’s College London, Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery

The microsystem is the small, immediate environment in which the child lives. This includes any relationships or organisations they interact with, such as family, caregivers and school. How these groups or organisations interact with the child will have an effect on how the child grows and develops: the more encouraging and nurturing those relationships and places are, the better the child will be able to grow. Furthermore, how a child acts or reacts to those people in the microsystem will affect how they treat the child in return. Each child’s genetic and biologically influenced personality traits (e.g. temperament) may end up affecting how others treat them (and how children respond).

The mesosystem describes how the different parts of a child’s microsystem work together for the sake of the child. For example, if a child’s caregivers take an active role in the child’s school – such as going to parent-teacher meetings or promoting children’s positive social/peer activities, such as sports participation – then this will help ensure the child’s overall growth. By contrast, if the parents or carers disagree between themselves about how best to raise the child and give the child conflicting lessons, then this will hinder the child’s growth in different developmental domains.

At the exosystem level are other people and places that are likely still to have a large effect on the child, even though the child may not interact with them very often. These will include extended parents’ workplaces, family members, and the neighbourhood and community, etc.

The macrosystem represents the largest and most remote set of people and things, but which may still have a great influence on the child’s developmental outcomes. The macrosystem includes factors such as government policies, cultural values and the economy, etc.

The interplay between a child’s genetic makeup and the environments within which the child develops is also acknowledged within this perspective.

Key factors in the developmental-ecological model include:

- children’s development is influenced by many factors – these include internal factors, such as their temperament, and external factors such as input from parents and others

- each child is an individual

- children develop along different dimensions simultaneously

- milestones are an important concept but should be used within a context that recognises each individual’s potentialities

- children influence their own development through their behaviour and transactions with others

- with help and support, children can recover from abuse or other negative experiences (The Developing World of the Child: Seeing the child, p5 – Open University et al, 2007).

Developmental psychopathology explores the origins and mechanisms that underlie mental disorders (such as depression, ADHD, anti-social behaviour, autism, schizophrenia). It recognises that an early experience (such as maltreatment) can lead to multiple outcomes (such as anxiety, depression, conduct problems) while multiple early influences (such as smoking in pregnancy, harsh early parenting) can contribute to a single outcome (such as conduct disorder).

This perspective highlights the importance of identifying factors that explain individual children’s different responses to specific risks and emphasises the importance of identifying mediating and moderating factors.

A mediating factor explains why an association may exist between a specific risk and risk-related outcome. A moderating factor underpins when a risk-related influence may affect a risk related outcome (e.g. harsh parenting practices affect child conduct problems when children are at specific genetic risk). So linked to this last example, developmental psychopathology recognises the importance of the interplay between biological risk (e.g. genetic and prenatal factors) and environmental factors (e.g. parenting practices) in explaining child and adolescent development, with the objective of informing the development of evidence-led intervention and prevention-based programmes (Cicchetti, 1984).

The importance of parenting and relationships

Each of the perspectives outlined above offer their own emphases as to the key influences on developmental outcomes. What is common across all perspectives, however, is recognition of the importance of each child’s environmental experiences – and of the family and parenting, in particular – on that child’s emotional and behavioural outcomes.

The quality and consistency of positive family relationship experiences have significant implications for children’s normal emotional and behavioural development”. Parental problems such as domestic violence, substance misuse, mental ill-health and learning disability can undermine parenting capability and have a long-term negative impact on children’s physical, cognitive, social, emotional and behavioural development that can last throughout the life course (Cleaver et al, 2011; Stanley, 2011; Taylor, 2013; Ward et al, 2014). In terms of children’s development, the impact of parental problems will vary according to the age of the child. The role of the family in psychological development – in particular, parent-child and inter-parental relationships – is a developing area of research.

Parent-child relationships: The emotional tone of the parent-child relationship is a fundamental factor in predicting children’s long-term emotional and behavioural development (Harold and Leve, 2012). While research has tended to focus on the mother-child relationship, the role of fathers is increasingly recognised as an important influence (Harold et al, 2013). For instance, where fathers are actively engaged in family-focused interventions (including maternal parenting-focused programmes such as Family Nurse Partnerships) research suggests that the likelihood of sustained positive outcomes in children is increased (Cowan and Cowan, 2008).

Inter-parental relationships: A range of studies show that children exposed to frequent, intense and poorly resolved inter-parental conflict are at increased risk for a variety of negative psychological outcomes, including depression, aggression, antisocial behavior, drug use and poor academic attainment (Harold et al, 2007). And where levels of inter-parental conflict are high, children are not only directly affected by the experience of acrimony between parents, but parenting practices are in themselves disrupted (Harold et al, 2012).

Genetic vs environmental factors

Since most research with families has studied biologically related parents and children, it has been difficult to understand the relative significance of genetic vs environmental factors in children’s developmental outcomes. However, recent studies have addressed this question by studying parents and children who were not genetically related. One study of children adopted at birth (Mannering et al, 2011) examined the direction of effects between parental relationship instability (e.g. general quarrelling and relationship dissatisfaction) and children’s sleep problems (e.g. restlessness and irritability) when children were 9 months and 18 months respectively. Researchers found that parental relationship instability when children were 9 months old predicted children’s sleep problems at 18 months. Children’s sleep problems did not predict parental relationship difficulties, thereby allowing the conclusion that relationship problems affect children’s early sleep patterns (critical for early brain development), not the other way around.

Whichever theoretical lens is applied draws our attention to the fact that children’s development takes place in an ‘environment of relationships’ (NSCDC, 2009). As the report of the Care Inquiry put it:

‘The relationships with people who care for and about children are the golden thread in children’s lives.’ (The Care Inquiry, 2013)

Quality relationships matter more than anything else in supporting children’s development – and for children in the care system, relationships within the birth family are not sufficient for securing well-being and optimum development. Social workers need to work with carers, birth parents and wider family and with prospective adopters to nurture positive relationships, sustain relationships for children placed away from home and provide long-term help and support.

Key questions for the child’s social worker

Key questions for the child’s social worker

![]() Download these notes as a PDF:

Download these notes as a PDF:

DfE Topic 3 Child Development Final 17/10/14 Combined notes

![]() Download these notes as a Word document:

Download these notes as a Word document:

DfE_Topic 3 Child Development Questions Final_02/09/14

Download the questions and exercises as a Word 97-2003 DOC file:

DfE_Topic 3 Child Development Questions Final_02/09/14 Word 97-2003

Methods

Suitable for self–directed learning or reflection with a colleague or supervisor.

Learning Outcome

Review your understanding of child development and identify actions you can take to support a child’s healthy development.

Time Required

Two sessions of 45 minutes

Process

Thinking of your current approach, answer the following questions:

- What is your understanding of child development from birth to adolescence and beyond? (see Research in Practice Child Development Chart and NSPCC The Developing World of the Child: Seeing the Child)

- What is your understanding of the impact of parental problems, such as domestic violence, substance abuse, mental ill-health and learning difficulties, on children’s development? (see Cleaver, Unell, Aldgate (2011) Children’s Needs- Parenting Capacity)

- How do you ensure that you have a good knowledge and understanding of the impact of maltreatment on children’s development? (See briefing 4 ‘Early brain development and maltreatment’ and briefing 2 ‘Attachment theory and research’.)

- What are your training and development needs in relation to child development?

- How do you ensure that you make the most of any training and development opportunities?

- How do you ensure that a child’s developmental progression is a key feature of assessments?

- What steps do you take to ensure that key aspects of development are included in the assessment?

- What steps do you take to gather information on children’s development from other professionals?

- How do you ensure that the assessment of the child informs support services and interventions for the child and that the child receives these services?

- What is your understanding on the theoretical perspectives of child development and their relation with interventions for children and families?

- What steps do you take to ensure that you take decisive action to ensure that children’s needs are met (including, if necessary removal from the birth family) within their developmental timeframe? (see briefing 6 ‘Impacts of delayed decision making’)

Key questions for the supervising social worker

Methods

Suitable for self–directed learning or reflection with a colleague or supervisor.

Learning Outcome

Review your understanding of child development and identify actions you can take to support a child’s healthy development.

Time Required

Two sessions of 45 minutes

Process

Thinking of your current approach, answer the following questions:

- What is your understanding of child development from birth to adolescence and beyond? (see Research in Practice Child Development Chart and NSPCC The Developing World of the Child: Seeing the Child)

- What is your understanding of the impact of parental problems, such as domestic violence, substance abuse, mental ill-health and learning difficulties, on children’s development? (see Cleaver, Unell, Aldgate (2011) Children’s Needs- Parenting Capacity)

- How do you ensure that you have a good knowledge and understanding of the impact of maltreatment on children’s development? (See briefing 4 ‘Early brain development and maltreatment’ and briefing 2 ‘Attachment theory and research’.)

- What are your training and development needs in relation to child development?

- How do you ensure that you make the most of any training and development opportunities?

- How do you help foster carers and adopters to understand children’s development and progress, particularly where there are problems?

- What steps do you take to signpost and facilitate access to support and interventions to help foster carers and adopters manage the child’s behaviour?

- How do you encourage and support foster carers (and adopters) to access specialist learning and development opportunities?

Key questions for social work managers

Methods

Suitable for self–directed learning or reflection with a colleague or supervisor.

Learning Outcome

Review your understanding of child development and identify actions you can take to support a child’s healthy development.

Time Required

Two sessions of 45 minutes

Process

Thinking of your current approach, answer the following questions:

- What is your understanding of child development from birth to adolescence and beyond and the impact of parental problems on this? (see Research in Practice Child Development Chart, NSPCC The Developing World of the Child: Seeing the Child, see Cleaver, Unell, Aldgate (2011) Children’s Needs- Parenting Capacity)

- To what extent does your team have a good knowledge and understanding of child development and the impact of parental problems on this?

- How do you ensure that you make the most of any training and development opportunities for yourself and your staff?

- How do you ensure that supervision sessions provide social workers with the space and opportunities to reflect upon their cases, in particular in relation to children’s development?

- Are you proactive in establishing effective partnerships with other services to facilitate information sharing?

- What support do you need from your organisation to improve these partnerships further?

- What steps do you take to ensure that there are a range of services available for children who may need additional support?

Key questions for foster carers and adopters

Methods

Suitable for self–directed learning or reflection with a colleague or supervisor.

Learning Outcome

Review your understanding of child development and identify actions you can take to support a child’s healthy development.

Time Required

Two sessions of 45 minutes

Process

Thinking of your current approach, answer the following questions:

- What is your understanding of child development from birth to adolescence and beyond? (see Research in Practice Child Development Chart and NSPCC The Developing World of the Child: Seeing the Child)

- What is your understanding of the impact of parental problems, such as domestic violence, substance abuse, mental ill-health and learning difficulties, on children’s development? (see Cleaver, Unell, Aldgate (2011) Children’s Needs- Parenting Capacity)

- What steps do you take to keep the child’s social worker informed of any progress or concerns around the child’s development?

- What steps do you take to ensure that the child accesses any specialist support he or she may need?

- What are your learning and development needs in relation to child development?

- What steps do you take to ensure that you access relevant training and development?

Presentation slide deck

Presentation slide deck

![]()

Download the slides as a PowerPoint .pptx file (3.5mb)

Alternative PowerPoint 97-2003 format:

DfE_3 Child development Final 17/10/14, Powerpoint 97_2003 format

References

References

![]() Download these notes as a PDF:

Download these notes as a PDF:

DfE Topic 3 Child Development Final 17/10/14 Combined notes

![]() Download these notes as a Word document:

Download these notes as a Word document:

DfE Topic 3 Child Development References Final_171014

Download the questions and exercises as a Word 97-2003 DOC file:

DfE Topic 3 Child Development References Final 17/10/14 Word 97-2003

- Aldgate J, Jones D, Rose W and Jeffery C (2005) The Developing World of the Child. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Brandon M, Sidebotham P, Ellis C, Bailey S and Belderson P (2011) Child and Family Practitioners’ Understanding of Child Development: Lessons learnt from a small sample of serious case reviews. (Research Report DFE-RR110) London: Department for Education

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979) The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Cicchetti D (1984) ‘The Emergence of Developmental Psychopathology’ Child Development 55 (1) 1-7

- Cleaver H, Unwell I and Aldgate J (2011) Children’s Needs – Parenting capacity. Child abuse: Parental mental illness, learning disability, substance misuse, and domestic violence. (2nd edition.) London: The Stationery Office

- Cowan P and Cowan C (2008) ‘Diverging Family Policies to Promote Children’s Well-being in the UK and US: Some relevant data from family research and intervention studies’ Journal of Children’s Services 3 (4) 4-16

- Davies C and Ward H (2012) Safeguarding Children Across Services. Messages from research. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Department of Health, Department for Education and Employment, and Home Office (2000) Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families. London: The Stationery Office

- Donnellen H (2011) Child Development Chart: 0-11 years. Dartington: Research in Practice

- Harold G and Leve L (2012) ‘Parents as Partners: How the parental relationship affects children’s psychological development’ in Balfour A, Morgan M and Vincent C (eds.) How Couple Relationships Shape Our World: Clinical practice, research and policy perspectives. London: Tavistock Centre for Couple Relationships

- Harold G, Aitken J and Shelton K (2007) ‘Inter-parental Conflict and Children’s Academic Attainment: A longitudinal analysis’ Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 48 (12) 1223-1232

- Harold G, Elam K, Lewis G, Rice F and Thapar A (2012) ‘Interparental Conflict, Parent Psychopathology, Hostile Parenting, and Child Antisocial Behavior: Examining the role of maternal versus paternal influences using a novel genetically sensitive research design’ Development and Psychopathology 24 (4) 1283-1295

- Harold G, Leve L, Elam K, Thapar A, Neiderhiser J, Natsuaki M, Shaw D and Reiss D (2013) ‘The Nature of Nurture: Disentangling passive genotype-environment correlation from family relationship influences on children’s externalizing problems’ Journal of Family Psychology27 (1) 12-21

- King’s College, London, Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery How children develop: principles and patterns of child development. Available online: http://keats.kcl.ac.uk/pluginfile.php/737715/mod_resource/content/1/page_07.htm

- Mannering A, Harold G, Leve L, Shelton K, Shaw D, Conger R, Neiderhiser J, Scaramella L and Reiss D (2011) ‘Longitudinal Associations between Marital Instability and Child Sleep Problems across Infancy and Toddlerhood in Adoptive Families’ Child Development 82 (4) 1252-1266

- Munro E (2011) The Munro Review of Child Protection. Interim Report: The child’s journey. London: Department for Education

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2009) Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships: Working paper 1. Cambridge, MA: Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University

- Open University, Department for Children, Schools and Families, Royal Holloway University of London and NSPCC (2007) The Developing World of the Child: Resource pack. Leicester: NSPCC

- Rutter M (1981) Maternal Deprivation Reassessed. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books

- Schofield G and Simmonds J (2013) Curriculum Framework for Continuing Professional Development (CPD) on Planning and Supporting Permanence: Reunification, family and friends care, long-term foster care, special guardianship and adoption. London: The College of Social Work.

- Séguin L, Nikiéma B, Gauvin L, Zunzunegui M and Xu Q (2007) ‘Duration of Poverty and Child Health in the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development: Longitudinal analysis of a birth cohort’ Pediatrics 119 (5) 1063-1070

- Stanley N (2011) Children Experiencing Domestic Violence: A research review. Dartington: Research in Practice

- Stassen Berger K and Thompson R (1995) The Developing Person: Through childhood and adolescence. (4th edition.) New York, NY: Worth Publishers

- Sullivan A and Joshi H (2008) ‘Child Health’ in Hansen K and Joshi H (eds), Millennium Cohort Study, Third Survey: A user’s guide to initial findings. London: Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education

- Taylor A (2013) The Impact of Parental Substance Misuse on Child Development. (Frontline briefing.) Dartington: Research in Practice

- The Care Inquiry (2013) Making Not Breaking. Building relationships for our most vulnerable children. London: Nuffield Foundation

- Ward H, Brown R and Hyde-Dryden G (2014) Assessing Parental Capacity to Change when Children are on the Edge of Care: An overview of current research evidence. (Research Report DfE RR 369) London: Department for Education

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid M and Stoolmiller M (2008) ‘Preventing Conduct Problems and Improving School Readiness: Evaluation of the Incredible Years Teacher and Child Training Programs in high-risk schools’ Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 49 (5) 471-488

- Williams N, Mughal S and Blair M (2008) ‘Is My Child Developing Normally?’: A critical review of web-based resources for parents’ Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 50 (12) 893-897